Stager during WWII.

Photo probably taken in Myitkyina District, Upper Burma.

Kenneth E. Stager died a few weeks ago at the age of 94.

I treasure the opportunity I had to meet him.

Tracking him down wasn't easy. In retirement he was too busy to answer letters. I can't blame him.

When I wrote to him in 1998, I was intensively researching biological exploration of pre-independence Burma.

Stager had been a soldier in the China-Burma-India theater during WWII. His job was to collect birds and mammals, screen them for

trombiculid mites, and prepare them as voucher specimens for the United States Typhus Commission.

What does that have to do with war?

Well, there was a race going on to crack the epidemiology of tsutsugamushi (Japanese:

dangerous bug) disease, or

scrub typhus.

The disease took more lives than combat, and sore-covered typhus survivors were in for a long recovery.

Solving the epidemiological riddle would give a leg up to either the Japanese or the allies.

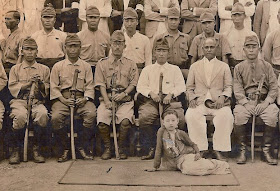

Japanese regimental picture from Upper Burma, WWII.

Photo probably taken after the British and Indian evacuation of Burma.

(Author's collection)

I knew little about the Typhus Commission back in '98, but Stager's specimens in the Smithsonian's National Museum stirred my imagination.

Each was a piece of history and part of a story that I wanted to know.

I found that Stager was living in retirement in Los Angeles, but my telephone messages were never answered.

So I wrote him a letter.

Months passed, and I had pretty much given up hope when a young colleague at the National Zoo told me Ken Stager had called about my letter.

Talk about a small world. My colleague Jesus Maldonado knew Stager very well.

The old curator apologized for failing to respond, and promised to tell me about his Burma days.

A few months later I had business in San Diego, and made an appointment to spend a day with him at the Los Angeles County Museum.

It was 1999. Stager was 83 years old and Emeritus Curator of Ornithology and Mammalogy.

Kachin regimental manao (festival) in 1950.

Photographer unknown. (Author's collection)

We spent a great day together, and I tape recorded an oral history of his days as a soldier-mammalogist.

He had an amazing memory and clarity of diction, and listening to him was like reading a great book.

So how did his orders change from foot soldier to mammal skinner?

Here's his story.

There was a company of

Kachin levies attached to the battalion in Myitkyina (pronounced Micheena) District, under the command of an Anglo-Burman named Jack Girsham.

Girsham had been raised in the jungle and grew up hunting. Before the war he had worked for the Bombay Burma Trading Corporation as a shooter of tigers and rogue elephants.

Jack Girsham, Stager's friend from Typhus Commission days.

(Photographer unknown)

The Kachins didn’t care for k-rations, so they supplemented their table with jungle fowl and pheasants snared in the surrounding hills.

One morning Stager found them returning to camp with "a beautiful adult male silver pheasant".

He saw only one thing -- a precious zoological specimen about to be plucked.

The Kachins saw breakfast.

As any zoologist can understand, unceremoniously plucking that specimen was a disturbing thought.

Stager requested Girsham, who spoke Kachin, to negotiate a deal. The result was that Stager could skin the bird if the Kachins got the carcass.

When the Japanese started shelling he jumped into a trench with the half-skinned bird.

And when the skirmish ended he requested cotton from the medical sergeant.

"Why?" asked the sergeant.

Stager convinced him that skinning birds was a legitimate war-related cause.

Not long afterward, Colonel Thomas Mackey, head of the Bowman Gray School of Medicine in N.C. arrived from the States to establish the US Typhus Commission, recently decreed by Executive Order.

Mackey summoned Stager, the word of whose strange habits had spread through the battalion.

He explained to the young soldier that he had brought a whole staff of specialists from the States, but had failed to get the mammalogist or ornithologist needed to survey bird and mammals for vectors of scrub typhus.

"I'm going to have you transferred."

Stager soon received his new orders, and made a case for having Girsham transferred too.

He and Girsham spent the rest of the war collecting mammals and birds for typhus research with a shot gun appropriated from the Chinese army. And they potted birds for mess whenever time permitted.

They made extensive collections of the fauna in the mountain rain forests north of Myitkyina using outboard motor boat and jeep transport. The unit moved to Yunnan for two months during a typhus outbreak in Kunming.

Typhus work ended several months after the Japanese surrender, and the Commission's results were published in various journals.

Most of the specimens went to the United States National Museum in Washington D.C., but some reside in the Los Angeles County Museum.

I asked Stager what became of the silver pheasant, and he said it was there in the museum.

That's when I took this picture.

Stager at the LA County Museum in 1998 holding the silver pheasant he finished skinning despite Japanese shelling.

(Photo by Chris Wemmer)

As I said, I treasure the opportunity I had to meet him.

There's a lot to learn from old guys who work in museums.

ReferencesAudy, J.R. 1968. Red mites and typhus. University of London, The Athlone Press.

[

a scholarly review of research on typhus and the accelerated investigations during WWII]

Girsham, J. with Lowell Thomas. 1971. Burma Jack. W.W. Norton and Company, Inc., New York

[

a good read, with a chapter devoted to Girsham's role in Merrill's Marauders.]

Mackie, T.T. et alia. 1946. Observations on Tsutsugamushi diesease (scrub typhus) in Assam and Burma. American Journal of Hygiene 43(3):195-218

Philip, C.B. 1948. Tsutsugamushi disease (scrub typhus) in World War II. Journal of Parasitology, 34(3):169-191.