Adventures in camera trapping and zoology, with frequent flashbacks and blarney of questionable relevance.

About Me

- Camera Trap Codger

- Native Californian, biologist, wildlife conservation consultant, retired Smithsonian scientist, father of two daughters, grandfather of four. INTJ. Believes nature is infinitely more interesting than shopping malls. Born 100 years too late.

Tuesday, March 30, 2010

Walking hay bale

Craig sent a photo the other day, and it was good news.

It looks like a hay bale after a long hard winter, but it wasn't.

It was a bodacious badger and a new species for our camera trap survey of the carnivores of Chimineas.

It revealed a bit more of itself in one other photo, but not much.

We hope to see more of Br'er Badger and its kin in the coming months.

Sunday, March 28, 2010

Seven months at Chimineas: habitat differences, species accumulation and discussion

Not the most commonly photographed mammal,

but one we could always identify.

This wraps up the analysis of the preliminary data collected by Craig Fiehler and me at Chimineas Ranch.

You'll be relieved to know that the next post will be usual fodder.

Number of species by habitat: The number of vertebrate species recorded in each habitat differed, with Blue Oak Woodland, Mixed Chaparral, and Annual Grassland having the largest numbers of species.

The number of mammal species also differed among habitats, and the order of abundance was similar to vertebrates in general except in Mixed Chaparral and Annual Grassland where the number of species was the same.

The differences in species numbers among habitats probably reflect uneven camera trapping effort among habitats, because species numbers and camera trapping effort have a correlation coefficient of 0.712.

Species accumulation over time: A pronounced stepwise distribution emerged when we plotted the cumulative number of species during successive weeks of the survey. The addition of 6 to 21 new species took place during weeks 1, 15, and 36, which coincided with camera deployment in new locations. Single species additions during successive weeks took place at the beginning and end of the 6-month survey. The stepwise pattern is unusual and probably a response to the appearance of bait at new locations. Gradual growth of the curve during recent weeks indicates that more additions can be expected, whereas a plateau indicates stasis.

Similar patterns of stepwise and gradual increases can be seen in separate curves for mammals and birds.

The stepwise accumulation of bird species took place at Poison Water Spring during only 8 days before the memory stick was filled. Large numbers of birds watered there in the morning and late afternoon.

Discussion and Conclusions

Camera performance: Camera performance was adequate, but false triggers and/or battery depletion and occasional camera failure significantly shortened the effective sampling periods. This is unavoidable because of the vagaries of PIR sensor technology. Active infra-red or laser sensors would be preferable for 24-hr sampling, though the external electrical wiring needed for these systems has inherent shortcomings, not least of which is its attraction to rodents which chew the wires. 24-hr camera sets in open-sky situations quickly filled the memory with false images, but high percentages of false triggers also took place in partially shaded areas.

It is desirable to reduce false triggers by judicious use of the night-time setting in partial shade and open sky situations. Where direct sunlight was absent, or limited for brief periods early in the day such as rock recesses, grottos, or large overhangs, PIR sensors worked very well, and captured excellent daytime portraits of coyote and a napping gray fox, and night time images of bats in flight.

Photo frequency trends: The use of baits undoubtedly increased the probability of detecting many species of mammals, with rodents showing a marked numerical effect during the first week. Photo frequency peaked on the night 4 but by night 8 had subsided to an oscillating baseline level. Carnivores on the other hand were attracted to the canned mackerel throughout the sampling period, and coyotes approached it even after two months by which time the odor of canned fish had become an overpowering stench.

These differences indicate that we need more data to discern species differences in response to camera trap baits.

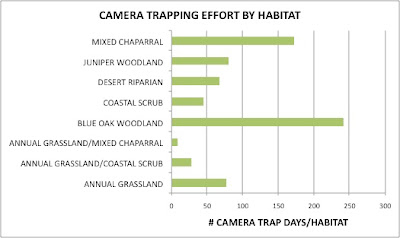

Survey effort: To date survey effort has been uneven across the seven habitats. Differences in habitat selection among carnivores are well documented. We need to increase survey coverage in under-represented habitats such as coastal scrub, desert riparian and juniper woodland in all seasons.

Four species of carnivores (coyote, gray fox, bobcat and black bear) were detected in the first eleven weeks of the survey, and the kit fox appeared on week 20. However, two normally abundant species were not detected.

The absence of striped skunks is unexpected because they are habitat generalists and respond readily to a wide variety of baits. Local extermination due to epidemic disease such as rabies seems unlikely, because contagion would likely have reduced populations of other carnivores (Carey and McLean 1983).

The absence of raccoons is also unexpected but may be explained by the small number of sets that were made in the vicinity of water.

The undetected status of ringtail and spotted skunk may be due to their patchy distribution in the region. Spotted skunks in Texas were found in older mesquite habitats (Neiswenter and Dowler 2007), and throughout their range they tend to occur in canopied or brushy habitats. These researchers found spotted skunks to be “more specialized in their coarse-grained utilization of habitat during foraging than striped skunks”, but they did cross open expanses less than 100 m to reach other patches of mesquite.

If present on Chimineas, spotted skunks may be found in more densely vegetated habitats such as coastal scrub, closed juniper woodland and mixed chaparral.

With few exceptions, mustelids are characteristically less often encountered than many other carnivores. Low densities and largely exclusive home ranges of badgers and weasels may explain their lack of detection. We expect continued sampling in grassland habitats, especially with active colonies of ground squirrels to reveal these species.

Finally, we made special efforts to detect ringtails by placing cameras in steep rocky areas and bluffs, but to no avail. The species is widespread in California and where it is most abundant in the Sacramento Valley it is often found in rimrock and bluffs bordering creeks and rivers (Orloff 1988). Though Orloff cites but two records of ringtails in San Luis Obispo County, they will likely be found in canyon riparian situations.

We will continue the survey through 2010 and intensify our efforts in underrepresented habitats.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Bob Stafford, Senior Cal Fish & Game Wildlife Biologist and Director of Chimineas Ranch for permission, enthusiasm and assistance in pursuing this study.

References

Carey, A.B. and R.G. McLean. 1983. The Ecology of Rabies: Evidence of Co-Adaptation. Journal of Applied Ecology, Vol. 20(3):777-800.

Neiswenter, S. A. and R. C. Dowler 2007. Habitat Use of Western Spotted Skunks and Striped Skunks in Texas. Journal of Wildlife Management, 71(2):583-586.

Orloff, S. 1988. Present distribution of ringtails in California. California Fish and Game, 74:196-202.

Thursday, March 25, 2010

Seven months at Chimineas: survey effort, habitat coverage, and species occurrence

Here's the second installment about our camera trapping findings at the Chimineas Ranch.

Survey effort over time: Camera trapping effort increased as more cameras became available during the survey. Effort was doubled during the latter half of the survey (October, November and December).

Survey effort and habitat coverage: Camera trapping effort as measured by camera trap days differed in the 8 habitats, with Blue Oak Woodland receiving the greatest effort, and Coastal Scrub receiving the least. The remaining three habitats, Juniper Woodland, Desert Riparian, and Annual Grassland and its variants received sub-equal camera trapping effort.

Twenty-six species of birds were also recorded, which represents a much smaller proportion (14.6%) of those known to be present on the unit. Ground foraging birds were among the most commonly recorded species, and carrion feeders were photographed only at the cow carcass.

Finally, Western fence lizards (4), Pacific tree frogs (6), and Western toads (23) were incidentally photographed at Poison Water Spring.

We're still not finished.

Don't want to waste any data, you know.

Tomorrow should wrap it up, then a brief discussion.

Wednesday, March 24, 2010

Seven months at Chimineas: camera performance and photo frequency trends

Camera Performance: Cameras were deployed for 1141 days (# cameras x number of days deployed). They were in operation for 723 days, or 42.3% of the days they were deployed. False triggers during 24 hr sets were usually responsible for the disparity. False triggers often filled memory cards to capacity and/or drained batteries in a few days.

68% of all photos from 21 comparable 24-hr sets (partial shade to open sky) were probably due mostly to heat-induced false triggers. The range was from 1.5 – 100%. False triggers probably due to rodents accounted for 58% of the photos from 6 night-time sets (range = 17.6 – 69.6%).

A total of 6965 photos were taken. 2977 of these (43%) contained vertebrates (including multiple species). This is equivalent to an overall 2.7 animal photos/24 hr.

Nocturnal versus diurnal activity: We tabulated the number of day and night visits for the 5 carnivores using data from 15 24 hr sets. The sample size is small but shows that with the exception of black bear most visits were nocturnal.

Photo frequency trends during sampling periods: The frequency of photos was not evenly distributed during sampling periods. At many sets more photos were taken during the first week.

Since this could be due to the greater number of cameras in operation during the first week, we plotted the mean number of photographs for rodents, and the trend was still evident.

To determine if this was a response to bait we plotted the mean number of bat photos per day at sets used as night roosts. Bait is not an attraction to these insectivorous bats. The correlation coefficient of 0.073 was low, and the slope was reduced.

The disappearance of bait is the most likely explanation for the declining visitation rate of rodents and also perhaps for some mammals other than bats.

Neither coyote nor bobcat showed the distinctive decline in photo frequency shown by rodents.

The daily distribution of visits by coyotes however shows a different pattern. At 10 camera sets low visitation prevailed most of the time, and highest visitation peaked between weeks 2 and 3. This is what Larrucea and her co-workers found: coyotes don't rush in to visit new cameras.

Bobcats showed two peaks of visitation during the first 2 weeks, but the pattern is not well defined.

Visitation data will increase in the coming months, and differences among species should become clearer.

Still awake?

Hey!! Don't tune out yet!

More graphs are coming, and after that you get to see photos from the cameras Craig just checked (including a new carnivore!).

Tuesday, March 23, 2010

Seven months at Chimineas

Last year I posted quite a few blurbs on Craig Fiehler's and my carnivore survey at the California Department of Fish & Game's Chimineas Ranch.

The purpose of the survey is to determine the distribution and relative abundance of mesocarnivores on the Chimineas Unit.

To do a proper survey we needed more cameras than I own, so we started modestly and conducted a pilot study.

The ranch is probably home to 12 species of carnivores, but only 10 of them have been confirmed.

The cast of characters includes the mountain lion, bobcat, black bear, raccoon, coyote, gray fox, kit fox, badger, striped skunk and long-tailed weasel.

Spotted skunk and ringtail should also be there, but no one has seen them (dead or alive), or collected voucher specimens.

A lot of data piles up in 8 months of camera trapping, but before reporting the results you should know what we did.

So let's start with methodology, which will be of interest mainly to field workers.

Cameras: We used a maximum of 16 homemade camera traps and one Cuddaback Trail Camera. The components of these “homebrew” camera traps were Sony s600 6 MP digital cameras and controller circuits made by Pixcontroller, Snapshot Sniper, White-tail Supply (XLP), or YetiCam. The controllers activate and trigger the cameras with passive infra-red (PIR) sensors. Controllers require 2- 3 seconds to power the camera and take the first photo, and the trigger successive photos at minimum intervals of 3 seconds.

Cameras were wired to supplemental batteries that normally insured operation for at least a month, and all components were housed in Pelican 1060 or 1040 camouflaged cases.

PIR sensors are highly responsive to air-borne temperature differentials, and on warm days moving vegetation and breezes rapidly fill a camera’s memory with false (blank) exposures. Consequently we set the cameras for both 24 hr and nighttime operation depending on lighting conditions.

Attractants: Cameras were mounted about 2 feet above ground on metal posts driven into the soil. Scents and/or bait were placed within each camera’s view to attract wildlife. Canned mackerel was the bait most often used. The tin was punctured on both ends and secured with rocks, wire or reinforcing bar. Scents were dabbed on vegetation, twigs, or rocks, usually at an elevated position to increase scent dispersal. We also set two cameras at a cow carcass for 2 nights.

Camera locations: We used Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to develop a property-wide grid system of 100-ha sample units. The 100-ha sample unit size was chosen because it encompasses the minimum home range size of two target species: ringtail (Bassariscus astutus) and Western spotted skunk (Spilogale gracilis) (Zielinski and Kucera 1995). We set single remote camera traps in each of 4-12 100-ha plots during each sampling period. We assigned a number to each camera trap location and refer to the location and associated information as the camera trap set.

Schedule: We attempted to service and move cameras to new locations monthly, but occasionally weather conditions and other factors delayed the schedule. The mean duration of a camera set was 29 days (range: 1-68), and the mean operational duration was 21 days (range: 0.15-68).

Data analysis: GPS location, altitude, habitat and topographical features were recorded at each camera trap set (Appendix 4), together with other details such as bait and camera settings (24 hr or night time). Animal species, date, time, and individual jpeg number were tabulated for each set from photos downloaded to computer (Appendix 6).

Additional variables for each camera set included:

- Camera trap days: Camera trap day was a convenient measure of effort defined as 24 hrs of camera operation. Nighttime sets were calculated as half days, so that 30 days of camera operation yielded 15 camera trap days. When the camera’s batteries were dead upon collection, the duration was calculated from the day of the last photo. The percentage of all photos that were of animal subjects. Low success rates indicate that many images were false triggers due to weather conditions during daylight hours or rodent traffic at night.

- Success rate: The percentage of all photos that were of animal subjects. Low success rates indicate that many images were false triggers due to weather conditions during daylight hours or rodent traffic at night.

- Number of species: We were able to identify most vertebrates except for certain rodents of the genus Peromyscus and bats of the genus Myotis.

- Number of visits: Multiple photos of a species were usually clustered in time and considered a single visit. Photos of any species that were separated by more than one hour were considered separate visits. No effort was made to identify individuals. We did not calculate the number of visits by rodents because of the large number of photos obtained, uncertain identification and the range of interval durations.

That's enough for now.

In a few days I'll start posting the findings.

BBC's Camera Trap Photo of the Year Competition

Many thanks to Galen Rathbun for cluing me in to the BBC's camera trapping competition.

If you have a camera trapping project and want the world to know about it this is your chance for a little glory and a $3000 grant for your project.

The contest is geared primarily to field workers and researchers using camera traps to survey wildlife.

Maybe the doors will open in the future for purely recreational camera trappers who far outnumber the biologists.

There are three photo categories: new discoveries, animal behavior, and animal portraits.

Check out the site above.

And by the way, Galen and Francesco Rovero described a new species of elephant shrew based on Rovero's camera trap photos of the creature.

If you have a camera trapping project and want the world to know about it this is your chance for a little glory and a $3000 grant for your project.

The contest is geared primarily to field workers and researchers using camera traps to survey wildlife.

Maybe the doors will open in the future for purely recreational camera trappers who far outnumber the biologists.

There are three photo categories: new discoveries, animal behavior, and animal portraits.

Check out the site above.

And by the way, Galen and Francesco Rovero described a new species of elephant shrew based on Rovero's camera trap photos of the creature.

Friday, March 5, 2010

Another trashed camera unsolved

As you can tell, not much has been happening in my world of camera trapping.

Healing a torn tendon is a long process.

The tendon attaches and grows stronger while the rest of the body grows weak from inactivity.

So I have been on a data analyzing blitz for two months. My hard drives are clean and tightly organized. I can find everything, and I analyzed 4 years of data from 7 camera trapping sites.

So what does that have to do with the muddy camera pictured above?

Well, yesterday I had visitors.

Rich Tenaza and Dave Fletcher drove up from Stockton to hack cameras, and Rich gave me copies of his Cleary Reserve jpegs so I can finish the analysis.

Rich shut down his camera trapping operation at Cleary when he found the trashed camera seen above (one that I hacked) late last year.

The vandal thoroughly totaled the camera and case -- broke the glass windows on the Pelican case, tore out the camera, dragged it through mud and dropped it in a pool.

Rich is convinced it was the vile deed of a non-ursid camera trasher.

I have the feeling it was the innocent work of a non-human (=ursid) curious about the wonders of modern electronics.

Also, there was no bear guard on the camera, which wouldn't have stopped a human, but would likely have limited the activities of a bear.

It makes one long for those good days when the only surprise you got was a shaggy bear mooning the camera.

Regarding my recent silence, Craig now has a few cams out at Chimineas, and even though the place is too wet to hit the back roads some new material should be rolling in soon.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)